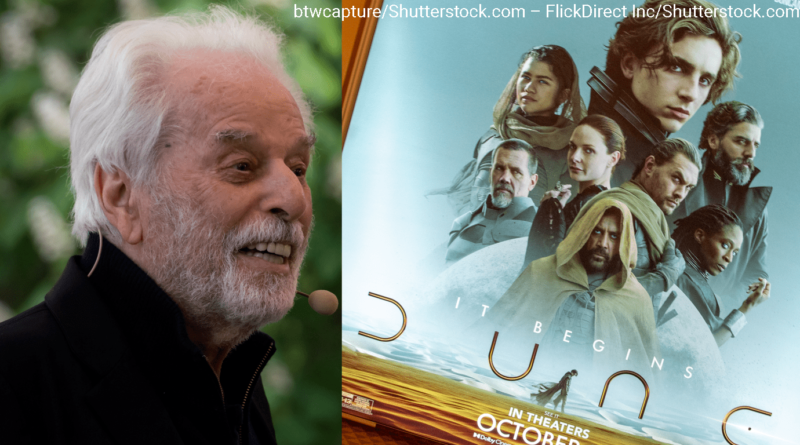

Jodorowsky’s Dune – The Greatest Movie Never Made?

As principal photography finished on Dune: Part Two only a few months ago, I decided to revisit the franchise. Although Denis Villeneuve’s adaptation of Frank Herbert’s science-fiction novel received nigh-universal acclaim, I am much more fascinated with another attempt at translating the book into film. While listening to Mark Kermode’s review of Dune, I was introduced to a supposedly failed Dune movie directed by avant-garde filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky. In the 1970s, he assembled an insane crew including Salvador Dalí, Orson Welles, and Mick Jagger. This piqued my interest and I decided to delve deeper into this bizarre story. Jodorowsky’s Dune, a 2013 documentary film by Frank Pavich, chronicles the adaptation’s history. It’s easily one of the most ludicrous tales in cinema history.

When casting news for Villeneuve’s movie surfaced, I was only vaguely aware of David Lynch’s reviled 1984 film and the original book. It takes place on the desert planet Arrakis, home to the universe’s most sought after commodity known as ‘spice’, a hallucinogenic drug that is required for space travel, as well as extending the user’s life and enhancing their mental capabilities.

We follow Paul Atreides, the young heir to the powerful House Atreides, as he interacts with the native population of Fremen, who want to take back their planet and its resources from the evil House Harkonnen.

Since its publication in 1965, the film rights have gone back and forth, with many trying their hand at adapting the influential sci-fi novel. However, it has always carried this reputation of being an unfilmable property, mostly due to the sheer breadth and depth of the source material.

The first proper pursuit of translating the book to film would be by Chilean-French surrealist director Alejandro Jodorowsky. Coming off the underground success of El Topo (1970) and The Holy Mountain (1973), Jodorowsky was hired to direct Dune by Jean-Paul Gibon. Considering the experimental and eccentric nature of his films, as well as a controversial style of filmmaking that included the alleged rape of an actress in El Topo, I fail to understand what exactly Gibon thought was going to happen with this adaptation.

Nevertheless, pre-production went ahead and Dune would prove to be Jodorowsky’s most grandiose endeavour yet. In a pre-Star Wars world, he was attempting to fabricate the effects of LSD and saw the film as a sort of “coming of a god…something sacred, free, with new perspective, to open the mind”, not unlike Dune’s spice.

Jodorowsky was willing to die for this production, seeing himself as a prophet ready to enlighten humanity. In order to accomplish this, he required a team of equally ambitious collaborators, whom Jodorowsky would affectionately call his “spiritual warriors”. The documentary contains various unbelievable anecdotes in this campaign to bring together his crew.

Jodorowsky wanted martial arts actor David Carradine, known for television series Kung Fu (1972-1975) and Tarantino-flick Kill Bill: Volume 2 (2004), to star as Leto Atreides (Paul’s father). He supposedly hired him after Carradine caught wind of his interest, came to see him, and chugged down an entire bottle of Jodorowsky’s vitamins in one go. Don’t ask me why.

He also approached the Rolling Stones’ Mick Jagger, at the peak of his fame, and German character actor Udo Kier, whom he met at Andy Warhol’s The Factory of all places. Both miraculously said yes.

However, it would prove harder to convince surrealist painting icon Salvador Dalí. Set to portray the emperor of the universe without any prior acting experience, Dalí agreed to do the movie under one condition: “I want to be the actor mas pagado (=highest paid) in Hollywood”. Dalí demanded $100.000 an hour, but they settled on a more ‘affordable’ $100.000 per minute of screen time, cutting it to about 5 minutes in total.

Another ‘warrior’ that required persuasion was Citizen Kane’s (1941) director Orson Welles, who at this point attained a reputation of excessive drinking and eating on sets. The movie’s villain would be the Baron, the monstrous and morbidly obese leader of House Harkonnen, whom Jodorowsky very flatteringly believed Welles to be a perfect match for. In order to lure Welles to the project, Jodorowsky offered to hire the chef of his favourite Parisian restaurant to cook for him every day, which proved successful.

To round out his cast Jodorowsky wanted his own son Brontis to play the lead role, but for this to be successful he deemed it necessary to train him as a warrior just like Leto had done Paul. For this movie that never got made, Brontis was taught martial arts by merciless stunt coordinator Jean-Pierre Vignau 6 hours a day, 7 days a week, for 2 years.

Jodorowsky also employed some of the most talented artists of the time to bring his ideas to life, resulting in some incredible concept art. Jean “Moebius” Giraud made 3000 fantastic drawings for the movie’s extensive storyboards. Dan O’Bannon was tapped to do VFX after Jodorowsky gave him “special marijuana” to explain his creative vision. Chris Foss designed the incredibly stylized spaceships, whilst HR Giger came on board to design the gothic Harkonnen home-world of Giedi Prime.

Interestingly, this group would eventually take their talents elsewhere and work on Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) instead. Pink Floyd and Magma were also hired to compose the music for Arrakis and Giedi Prime respectively.

Highlighting the vast number of extraordinary people participating in this pious journey, the documentary claims the movie would have changed the world. I find this to be doubtful though, especially considering the limits of 1970s filmmaking. As a result of Jodorowsky’s unwillingness to compromise on his desired 10–20-hour runtime, studios across the board (rightfully) declined to finance it.

Jodorowsky himself, too, was a risk, considering his earlier work. Fando y Lis (1968), for instance, incited a riot and was subsequently banned in Mexico. Fans are vocal about their longing for an adaptation that remains close to the source material, yet Jodorowsky claims he could not have such respect. He says “I was raping Frank Herbert, but with love”, something he seems to have a habit of doing.

Unsurprisingly, the movie did not get made, which may have been for the better. It makes for a better story told in a documentary format than the feature film would have ever been, although possibly just as fictional considering the amount of drugs everyone was on during the 70s. It also debunks Avengers: Endgame (2019) as being the most ambitious crossover event in cinematic history.

However, for those that are interested in what might have been, Jodorowsky’s plans were repurposed into a comic series called The Incal (1980-2014), which was revealed to be getting a live-action adaptation with Oscar-winner Taika Waititi at the helm. If you’ve already seen Villeneuve’s Dune, though, that’s great. But I seriously implore you to watch this documentary as well, as it is pure insanity. Although I dispute the influence this movie may have had, Jodorowsky’s ambition is admirable and unrivalled.

“I have the ambition to live 300 years. I will not live 300 years. But I have the ambition. Why do we not have ambition? Have the greatest ambition possible. You want to be immortal? Fight to be immortal. Do it. You want to make the most fantastic art of movie? Try. If you fail is not important. We need to try.” – Alejandro Jodorowsky