Daffodils, precious metals, angels and bullfighters

It’s a warm, radiant night, the 1st of March, 1935. Tonight, George Balanchine’s Serenade is to be performed for the first time at the Adelphi Theater, and the ballet enthusiasts of New York have gathered to watch the premier. It’s an abstract, plotless classical performance fashioned onto Tchaikovsky’s “Serenade for Strings in C op. 48.”

Kathryn Mullowny stars as the Dark Angel, the only character who is distinguished by name in the cast list. Her dress is evocative of the togas worn by angels in medieval art, flowing down to her ankles, which are bound in the satin ribbons of her shoes. The tips of her pointes lift her up from the polished floor, supporting the tips of her toes as they support her whole weight. The time comes when she has to bow to the rest of the Angels. Carefully she bends down, her legs the image of stillness while her waist folds, one arm extending to linger — almost floating — just above her right foot.

When she’s happy, she’s jubilant. When she’s angry, she’s furious. When she’s sad, she’s inconsolable. Expressions are choreographed, fine-tuned, and exaggerated through impossible contortions of flesh and muscle. Excessiveness and ballet go hand in hand, moving synchronically, like the four little swans in Tchaikovsky’s other famous ballet.

When attempting to define camp (an aesthetic originating in gay and trans subculture) in his novel The World in the Evening (1954), Christopher Isherwood brings up ballet as an example of its “high” variety. In the 1948–1950 production of Serenade, the male dancers donned blue tights and golden necklaces while the women twisted their bodies in ways unachievable by the average woman, yet they were still portrayed as the epitome of femininity. If ballet can be camp, then camp shares some of the qualities of ballet: an overplaying of life, an improvisatory take on gender that questions sexual truisms.

I can’t begin to define “campness.” It has been done before, time and time again by people far more knowledgeable than I: Christopher Isherwood (1954) has done it, Susan Sontag (1964) has basically written the book on it, while drag queen Trixie Mattel provided us with a brief introduction in Netflix’s I Like to Watch (2023) (with her co-host Katya insisting that camp is what you do when you sleep in a tent during the summer). Their definitions clash and collide in a dance; camp is said to be gender-defying, transgressive, often defying norms in a tongue-in-cheek and jovial way. Mikhael Bakhtin — the Russian literary theorist — proposed something similar. He used the word “carnivalesque” to describe moments in literature where dominant societal narratives are turned around through humor, changing “the serious into the frivolous” (Sontag 1964).

By extension, camp necessarily shares its theatricality, extravagance, and play-pretend quirks with cinema. James Bidgood’s film Pink Narcissus (1971) — a non-linear soft porno slash erotic visual poem slash classical allegory filled with pretty boys and glitter — is textbook 1970s camp. Tacky? At times. Beautiful? Always. Despite its blushing title, an illustrious aureate frame encases the movie: desire and beauty are accented by hazy reflections in golden mirrors, golden-lace-edged translucent curtains, golden hairspray, golden body paint, golden butterflies, and narcissus flowers — also known as daffodils — bearing their gleaming golden hearts to a very voyeuristic lens.

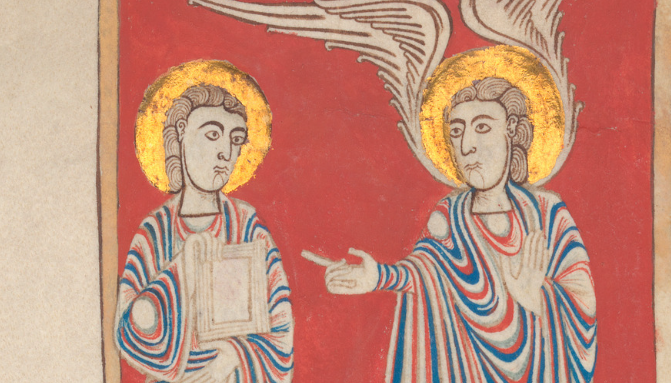

In the Middle Ages, gold was reserved for the One who gifts His own servants with “flocks, and herds, and silver, and gold […]” (Gen. 24:35 KJV). From glass mosaics to the garb of blue-blooded rulers, gold was divine, the hue produced by blurring earthly wealth and dreamy heavenly splendor. Though medieval people thought the throne of God to be carved from lapis lazuli, they painted Jesus’ robes — and the halos of his orders of angels — golden. In the Beatus manuscript, the angels’ faces are encircled in gold-leaf discs.

In their flaxen gleam, their androgyny strikes me. According to “angelologist” Peter Lamborn Wilson, being in the liminal space between the human and the heavenly requires sexual ambiguity (let alone an “exalted erotic state”). Until the 19th century, angels were beyond and above gender. They occupied the point I wish I could touch yet for one reason or another — perhaps for my inescapable mortality, which they lack — fall short of reaching: they are both and neither. In the Middle Ages, angels were beauty personified, which caused some conundrum, as — according to Wilson — women were associated with the ideal of beauty in the human world, which was embodied in religious imagery by feminine “male” angels.

It’s no surprise that, in the medieval Eastern Roman Empire, eunuchs were linked to angels, as people considered them to occupy a third gender (though they still used masculine pronouns for them). Gender ambiguity is not the only thing they shared; For their supposed similarity to God’s winged messengers, eunuchs were thought of as “pure,” meant in a very sex-negative way, as in all too capable from abstaining from the evils of sex.

A Byzantine legend has a man asking a weeping eunuch standing outside a brothel what’s wrong. “I am an angel”, replies the weeping man. He explains that he’s the assigned guardian angel of a person who’s “devoted” to a prostitute. He is actually crying at the image of demons he can see dancing around this person, laughing all the while. It is 99% certain the demons were not dancing ballet, but that would be a nice image, no?

In reality, Byzantine eunuchs were not so “pure.” Kaldellis tells us that, because of their inability to have kids, they were very popular among medieval women who were looking for pre- or extra-marital sex. Many of them occupied esteemed positions of power in the palace. We might imagine emperor Angelos and his second-in-command, himself a eunuch, accepting their guests into the Chrysotriklinion, or the “golden reception hall.” The banquet is exquisite. Angels are watching from golden murals, painstakingly glued onto the walls by the royal mosaicists. Daffodils adorn the royal dining table in pink vases.

In the 1993 Japanese poster for Pink Narcissus (1971), a silhouette of the protagonist hovers over a pair of yellow-tinted butterfly wings. Wings are, after all, a crucial element of what it is to be an angel — or a fairy. After all, apart from “jaundice,” “melancholy,” “glitter,” and “gall,” gold is etymological siblings with the Old English “galdor,” meaning spell or magic.

Angels elude time, species, and sex. Pink Narcissus, an experimental movie whose protagonist is at once a feminine boy, a butterfly, and a flower, seems to be permeated by an angelic essence. Narcissus is, like angels, noncorporeal, ageless, caught in a state of perpetual youth on our screens.

In another scene, the protagonist has slipped into a gold-covered bullfighter costume, worn over a red satin undershirt. Three years later, in 1974, the bullfighter image became again a point of gendered transgression, when Venezuelan Ángela Hernández demanded the annulment of an early 1900s law prohibiting women from becoming professional bullfighters. We can picture her in her grand costume in the middle of her arena, being kept safe by more than the angelic invocations of her name, and the blinding sparkle of her gold-striped shoulder-padded jacket.

She and Bobby Kendall, the star-flower of Pink Narcissus, are not the only angels of transgression and camp sensibility. Remember the dishevelled and sexually voracious angel from the 2017 production of Angels in America? What about Judas’ angelic gospel choir of backup singers in the ending of Jesus Christ Superstar (1974), sporting shiny white wigs and feather-boa sleeves, with Judas himself rocking a bell-bottomed, pure-white full bodysuit with fringed wings? Then there are also Warhol’s chubby, brilliantly pink cherubs (1952), or Felicia’s silver wings shining through the endless expanse of the outback in The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), as she lip-syncs to one of Violetta’s songs from Verdi’s opera La Traviata. In the second act, Violetta is praised for being “pure as an angel.”

This angelic genealogy extends as far back as the New Testament, where the Sons of God (the angels) come down to Earth and have sex with human women. Their offspring, the Nephelim, turn out to be a troublesome race, having learned from men the art of war and, from women, “the vanity of cosmetics” (Lamborn Wilson 1980). “Nephilim” is often translated as “fallen angels.” They are rebellious, and clouded in mystery. Resistance, artifice, drama and beauty — could that be a suiting definition of camp?

Sources:

- Anthony Kaldellis, A Cabinet of Byzantine Curiosities. Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Peter Lamborn Wilson, Angels. Thames and Hudson, 1980.

- Alastair Macaulay, “The genesis of Balanchine’s ‘Serenade’: a chronology and bibliography,” 2024, https://www.alastairmacaulay.com/all-essays/y1ra81n7bcpa4hp1y15cilgi85qx5a.

- Jessica A. Boon, “At the Limits of (Trans)gender: Jesus, Mary, and the Angels in the Visionary Sermons of Juana de La Cruz (1481-1534).” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, vol. 48, no. 2, 2018, pp. 261–300, https://doi.org/10.1215/10829636-4402227.

- “Serenade (ballet)” on Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serenade_%28ballet%29

- “*ghel-” (etymology of “gold) on Etymonline, https://www.etymonline.com/word/*ghel-#etymonline_v_52720

- Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp,’” 1964

- You can watch Pink Narcissus (1971) here!